The Ahnenerbe, officially known as the “Forschungs- und Lehrgemeinschaft das Ahnenerbe” (Society for the Study of the Heritage of Ancestors), was a German think tank founded in 1935 under the direct orders of Heinrich Himmler, a key figure in the Nazi regime and head of the SS. This organization was not merely an academic institution but a tool in Himmler’s grand ideological vision, blending pseudo-science, occultism, and Nazi racial theories into a singular mission.

Himmler, deeply influenced by romanticized notions of ancient Germanic and Aryan supremacy, sought to resurrect what he imagined as an idealized feudal past—a world where the so-called Aryan race would reign supreme in a meticulously reconstructed society echoing the grandeur of antiquity.

Himmler’s ambitions were strikingly practical in their execution. He envisioned the creation of Aryan villages across a postwar world, each designed to reflect the architectural aesthetics of the Roman era, which he believed resonated with the ancient Germanic spirit. One such experimental settlement, the model village of Mehrov, was constructed in East Berlin as a tangible manifestation of this dream. To lend authenticity to these projects, the Ahnenerbe relied heavily on archaeological findings—ancient stones, bones, pottery, and other artifacts—that purportedly illuminated the lives of prehistoric Germans. Among the prominent figures in this endeavor was Assien Bömers (1912–1988), a young archaeologist whose work gained traction within Nazi circles. Bömers boldly claimed he could trace the “Nordic” lineage of the German people back to the Paleolithic era, a time when woolly mammoths roamed the European landscape, thereby reinforcing the Nazi narrative of an ancient, superior Aryan ancestry.

However, the trajectory of the Ahnenerbe shifted dramatically in early 1937 when Himmler initiated a sweeping reorganization. The organization’s initial focus on historical and archaeological research gave way to a more esoteric and ideologically charged mission: the search for divine ancestors whose existence would substantiate the notion of German racial superiority. This pivot aligned closely with Adolf Hitler’s worldview, which divided humanity into three distinct categories: the founders of culture, the bearers of culture, and the destroyers of culture. Hitler identified the Aryan race—characterized by tall stature, blond hair, and blue eyes—as the founders, crediting them with the creation of art, science, music, literature, and all significant cultural advancements throughout history. The “destroyers,” in his estimation, were implicitly the Jewish people and other groups deemed inferior. Modern Germans, Hitler asserted, were the direct descendants of this ancient Aryan race, and Himmler was determined to provide evidence to support this claim, lest he disappoint his Führer.

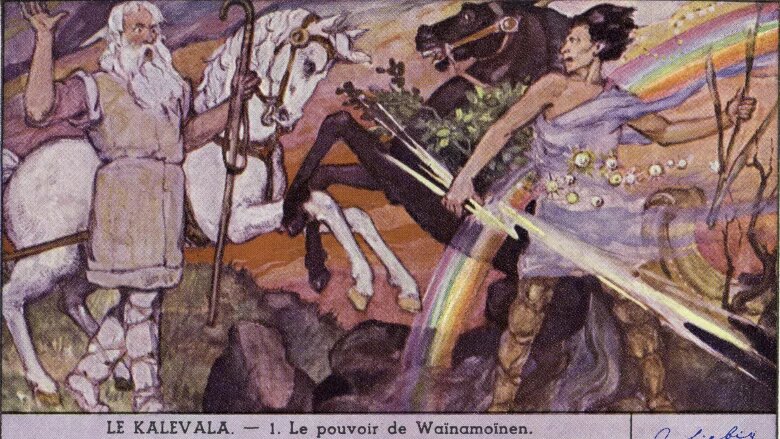

The Ahnenerbe’s early expeditions reflected this blend of historical curiosity and ideological zeal. One such venture took researchers to Finland to explore the origins of the Kalevala, a 19th-century epic poem rooted in Finnish folklore. The Kalevala captivated Nazi imaginations with its tales of heroes, seers, prophets with supernatural abilities, and a mythological framework encompassing the creation of the world, royal lineages, and the roots of paganism—complete with an otherworldly mill churning out salt and gold. Expedition members meticulously documented mystical chants, spells, and rituals, hoping to replace Christian ceremonies with what they considered more “authentic” Aryan rites.

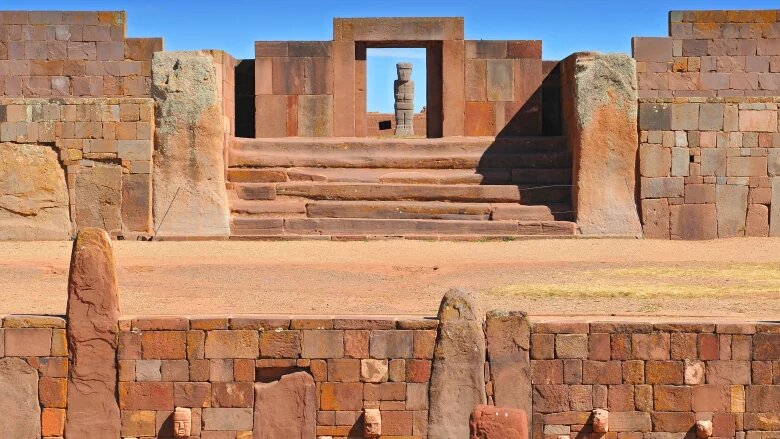

Though the Bolivia expedition was ultimately aborted due to the outbreak of World War II, the Ahnenerbe pursued other fantastical quests: searching for giant skeletons in Tanganyika (modern-day Tanzania), seeking the mythical jinn city of Zerzura in Libya, dispatching Otto Rahn to hunt for the Holy Grail in locations as far-flung as Iceland, and scouring the globe for the Ark of the Covenant. By 1938, the organization’s gaze turned eastward to Tibet, where an expedition led by Ernst Schäfer would become one of its most infamous undertakings.

The Tibetan Expedition

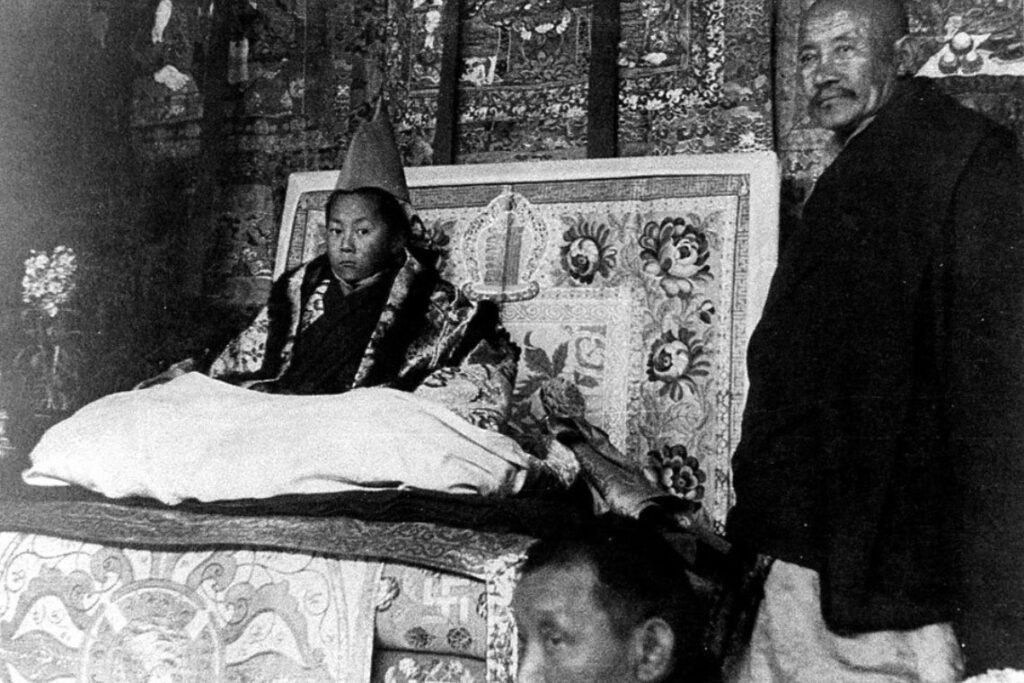

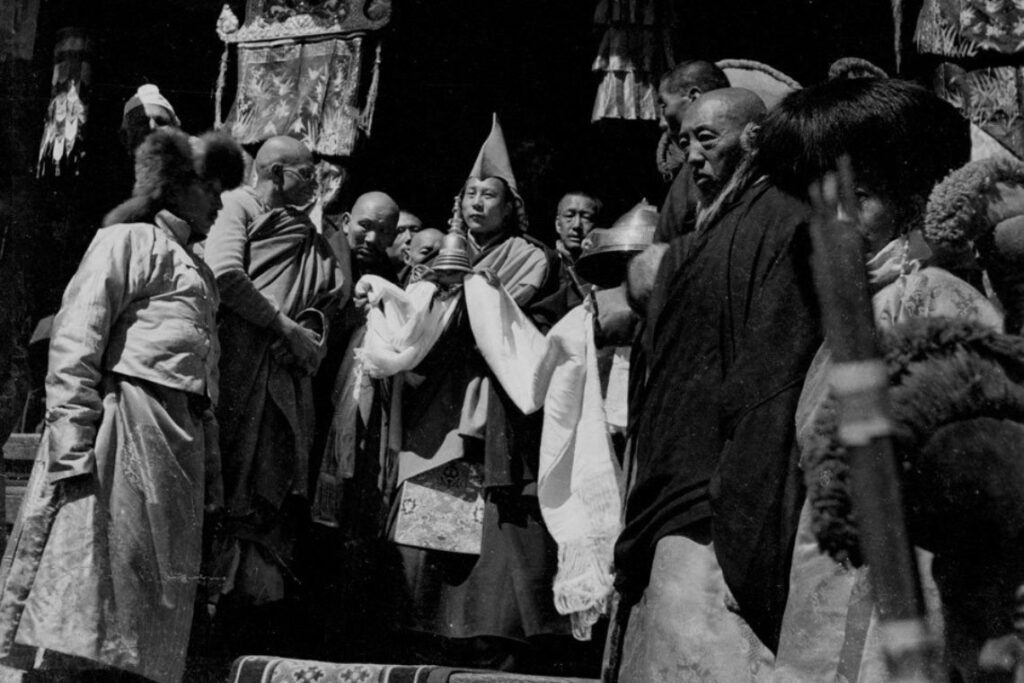

The backdrop to the Ahnenerbe’s interest in Tibet was shaped by both geopolitical and mystical factors. In 1933, the 13th Dalai Lama passed away, leaving his successor, Tenzin Gyatso—born in 1935 and later known as the 14th Dalai Lama—as the spiritual and political leader of Tibetan Buddhism. Too young to govern, the Dalai Lama’s authority was entrusted to a regent, who unwittingly welcomed German visitors harboring a supremacist agenda. The Nazis viewed Tibetans, along with Buddhists and Hindus, as racially inferior, believing that the “pure” Aryan bloodline—allegedly originating from Atlantis—had been diluted through intermarriage with native populations some 1,500 years prior.

Tibet held a particular allure for the Nazis due to its cultural symbols, notably the swastika. Known to Tibetan Buddhists as the “yungdrung,” this left-facing swastika symbolized good fortune and eternity, adorning homes and monasteries across the Tibetan Plateau long before its appropriation by the Nazi Party. This shared iconography fueled speculation about ancient connections between Tibet and the Aryan race, a notion Himmler eagerly embraced.

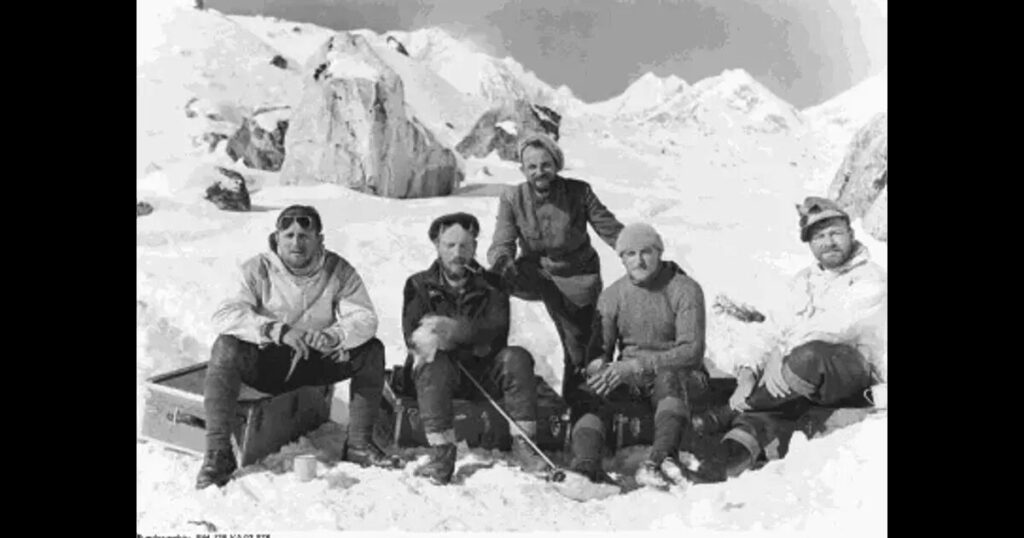

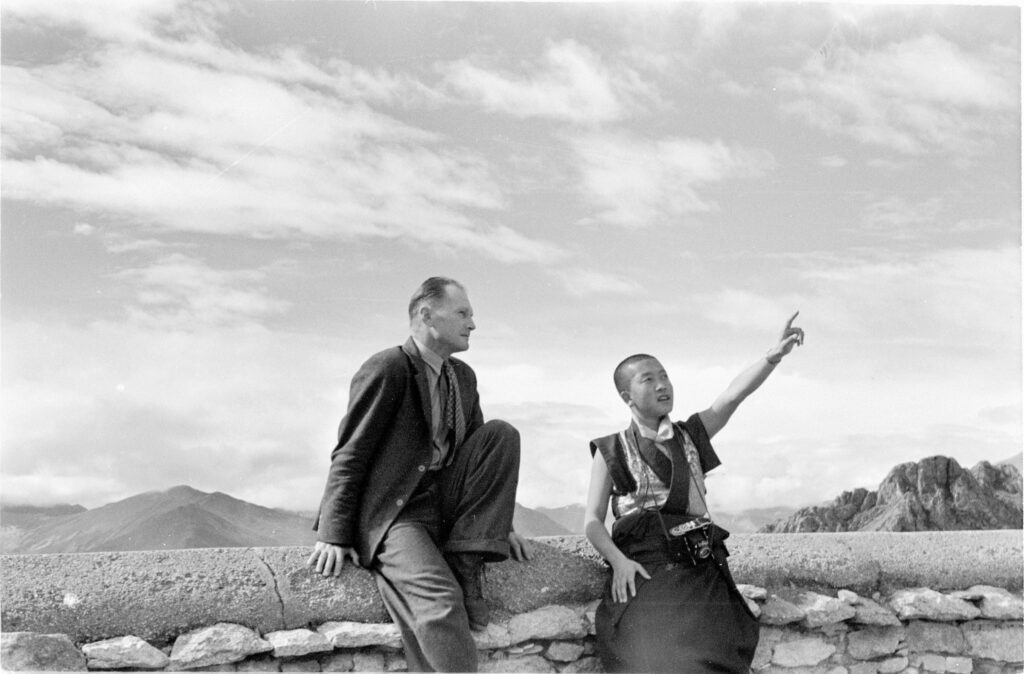

The 1938–1939 Tibetan expedition, ostensibly a scientific endeavor, was deeply entangled with Nazi politics and pseudo-science from its inception. Ernst Schäfer, a zoologist and geologist by training, led the mission, which Himmler sought to co-opt under the Ahnenerbe’s banner. Himmler, captivated by Asian mysticism and concepts like karma, saw Tibet as a potential repository of Aryan secrets. He insisted that Schäfer incorporate Hans Hörbiger’s “World Ice Theory” into the expedition’s research—a fringe hypothesis positing that Atlantis was destroyed by a catastrophic collision between Earth and an icy moon. Schäfer, however, resisted these esoteric directives, prioritizing a comprehensive scientific survey of Tibet that integrated geology, botany, zoology, and ethnology.

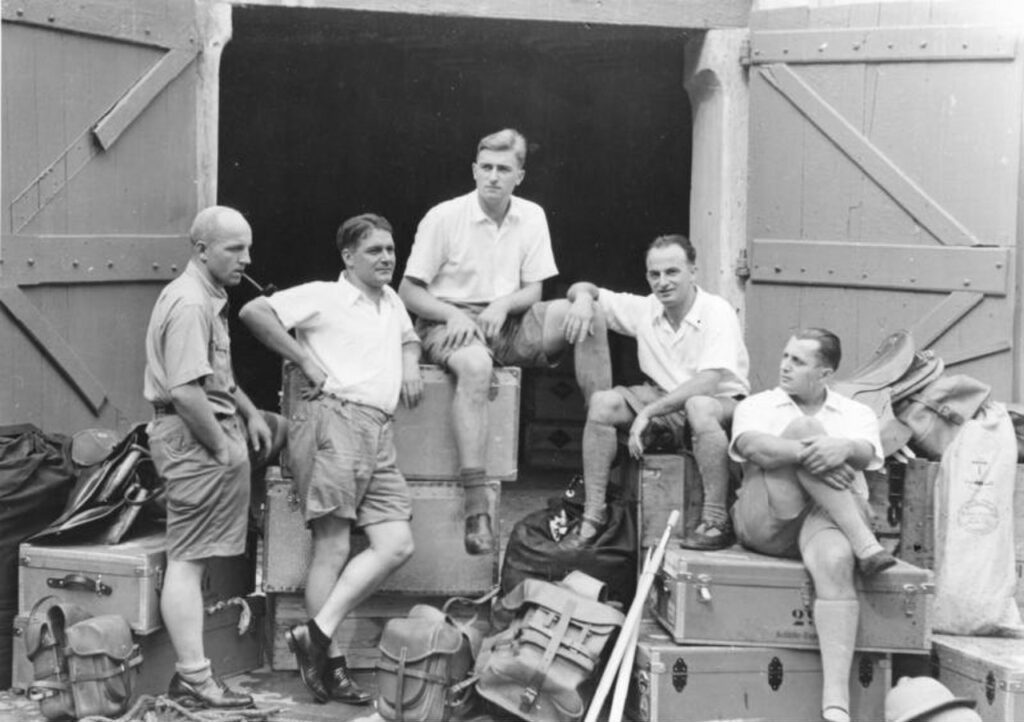

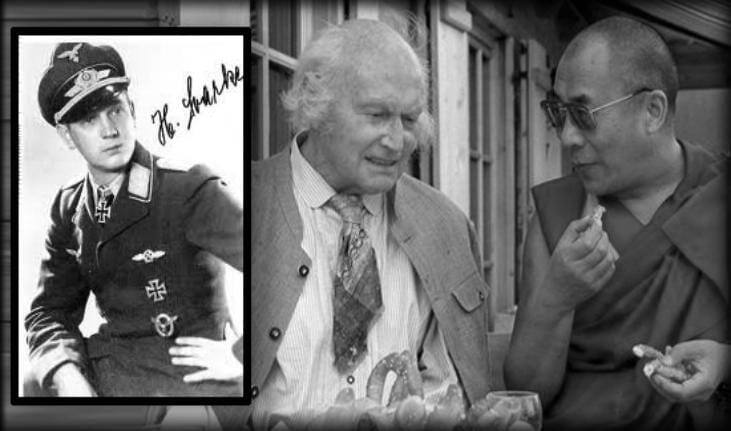

Organizing the expedition proved a Herculean task. Schäfer faced logistical challenges, funding shortages, and political pressures from both Himmler and the British authorities governing access to Tibet via India. Himmler’s support came with strings attached: all expedition members were required to join the SS, tethering the mission to the Nazi apparatus. Despite these constraints, Schäfer assembled a small but skilled team: himself as the leader and mammologist-ornithologist; Ernst Krause, an entomologist and photographer; Bruno Beger, an ethnologist and racial anthropologist; Karl Wienert, a geophysicist; and Edmund Geer, the caravan’s technical overseer.

The expedition departed in spring 1938, arriving first in Calcutta amid a diplomatic firestorm. A German propaganda outlet, Völkischer Beobachter, hailed the mission as an “SS Expedition to Uncharted Tibet,” prompting the Indian press to decry it as a “Nazi Invasion.” These headlines complicated Schäfer’s negotiations with British officials, who remained wary of espionage despite his assurances of scientific intent.

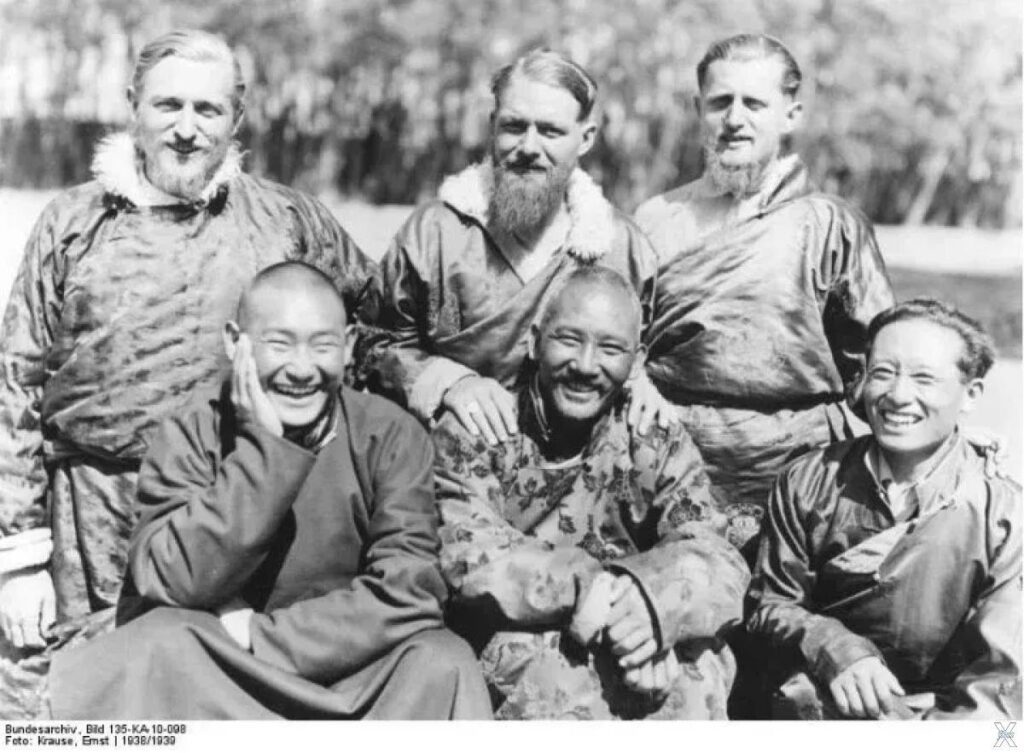

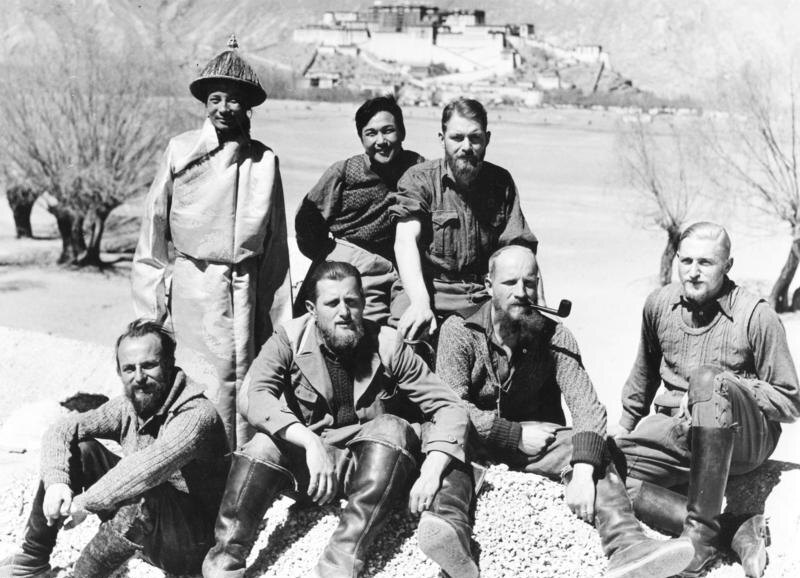

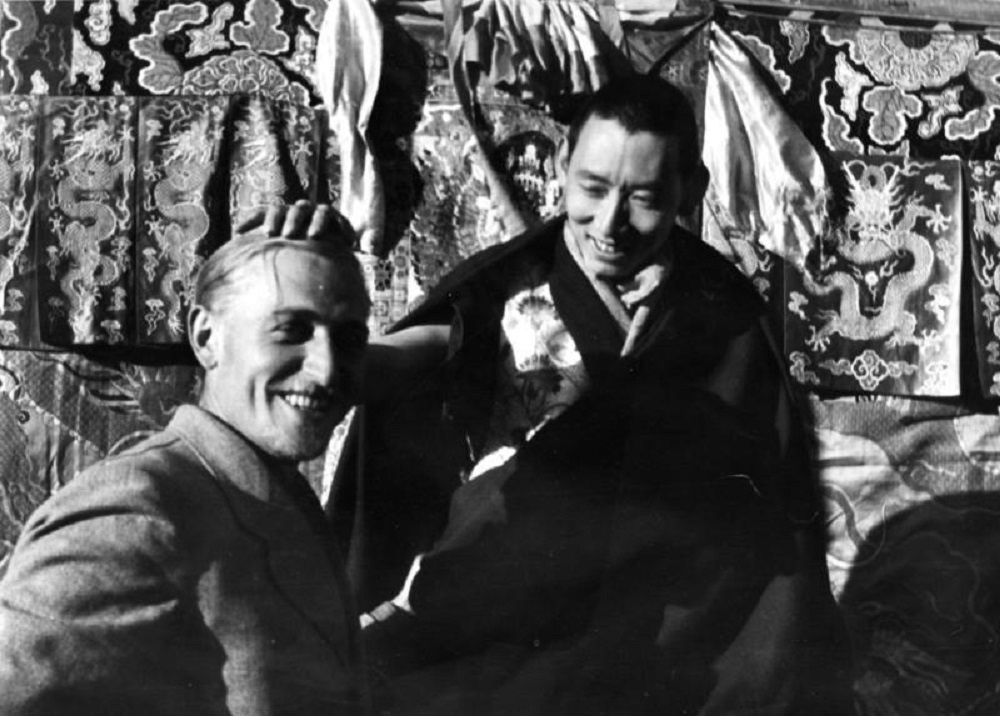

After months of delays and repeated denials from the Tibetan government, the team finally entered Lhasa in early 1939, securing a two-month stay. There, they forged official ties with the Kashag (Tibet’s governing council) and the regent, Reting Rinpoche, while cultivating relationships with local aristocracy.

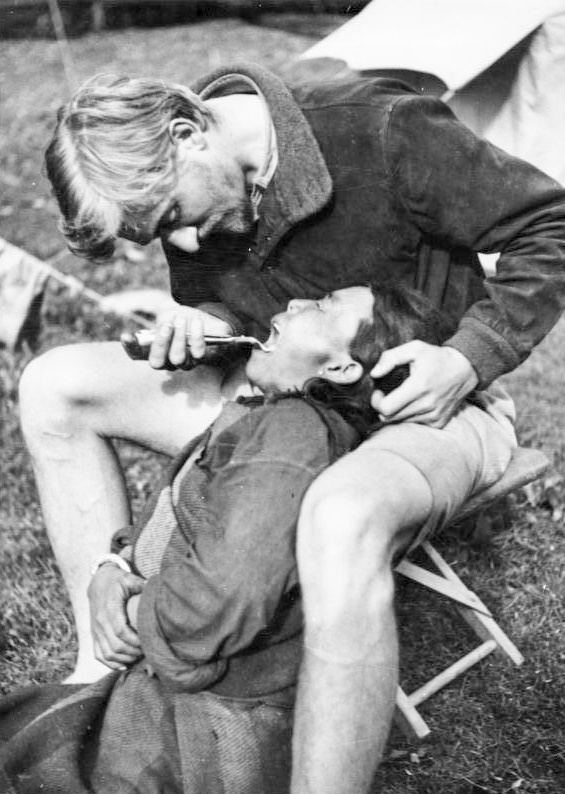

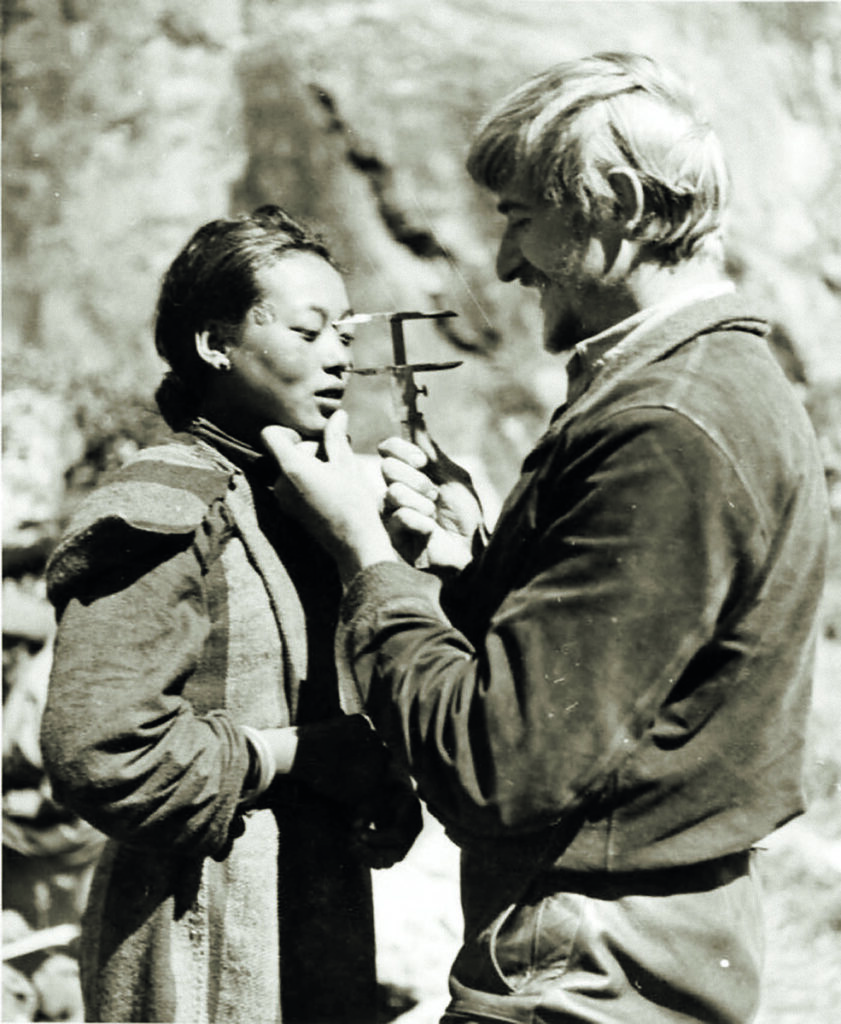

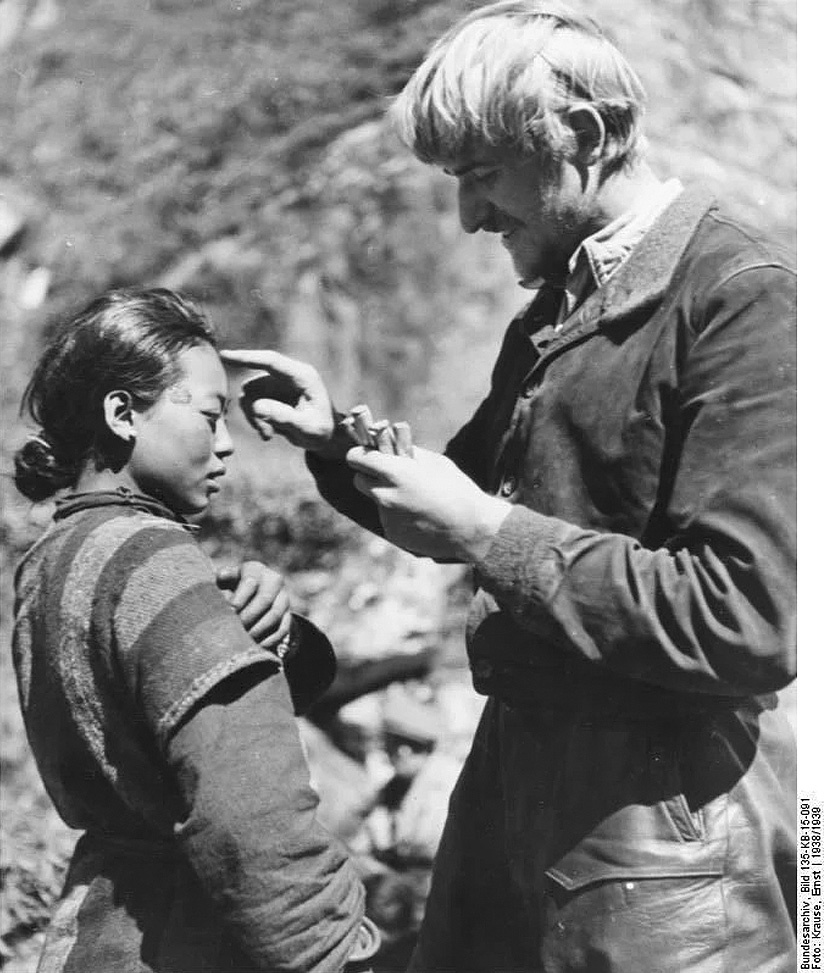

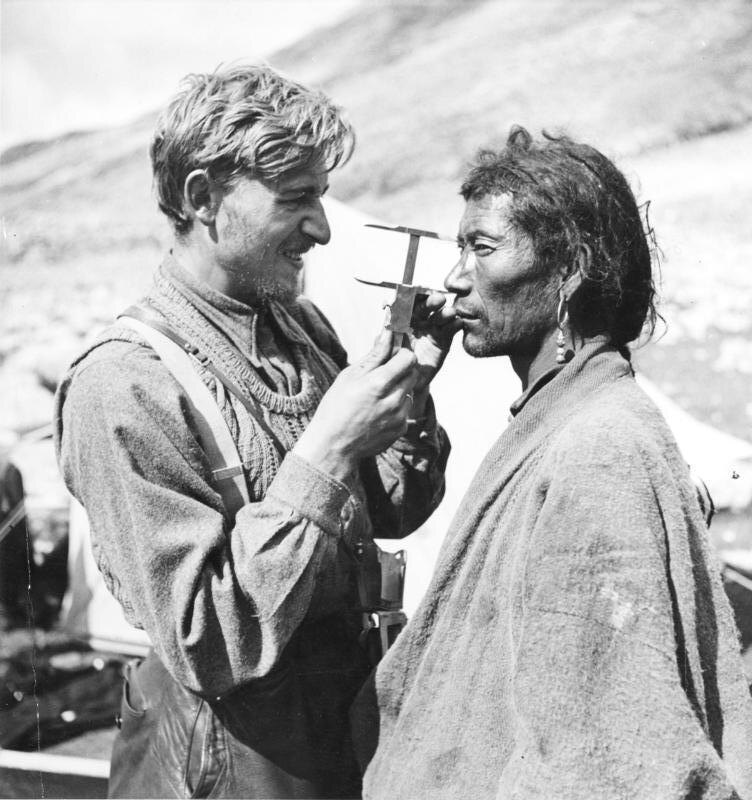

Bruno Beger emerged as a central figure during the Lhasa sojourn, conducting extensive anthropological studies on the Tibetan populace. His work focused on racial measurements—cranial and facial dimensions, casts of heads and hands, fingerprints, and palm prints—intended to explore supposed links between Tibetans and the “Nordic” race.

Beger examined 376 individuals, created casts from 17 others, and collected a trove of biological and cultural data. The team also amassed an eclectic array of specimens, from plants and animals to archaeological relics, all destined for Germany.

Return and Legacy

The expedition concluded in August 1939, just weeks before Hitler’s invasion of Poland ignited World War II. Himmler declared the mission a triumph, asserting it confirmed the Aryan settlement of Tibet. Schäfer was rewarded with a promotion and a dedicated Ahnenerbe department, though his postwar fate diverged from his Nazi patrons. Arrested in 1945, he was released in 1949, later teaching in Venezuela before returning to Germany as a museum curator.

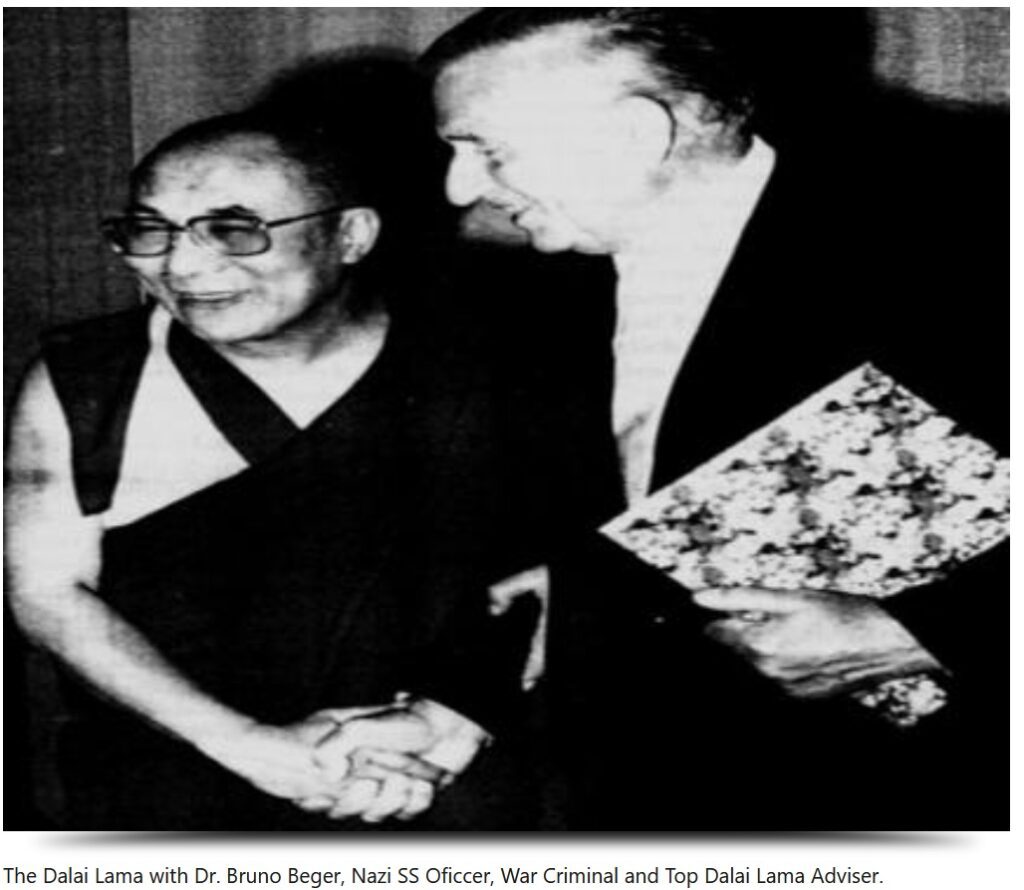

Beger’s story took a darker turn. Before Tibet, he headed a racial identification unit at RuSHA, targeting Jews for persecution. Post-expedition, he selected 86 Jewish prisoners at Auschwitz for a gruesome skeletal collection, leading to their murder at Natzweiler-Struthof. Though tried in 1970 and convicted as an accessory to these killings, Beger’s three-year sentence was suspended on appeal.

As the Third Reich crumbled, Ahnenerbe members destroyed incriminating records, but Schäfer’s Tibetan artifacts survived, hidden in a Salzburg castle until their 1945 discovery. The organization’s pseudo-scientific theories lingered, later exploited by far-right groups.

The Tibetan expedition, meanwhile, spawned enduring myths—tales of Nazi-Buddhist alliances and Tibetan monks in Berlin—blurring the line between history and fantasy in the annals of Nazi occultism.