In the sun-baked plains of southern Iraq, where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers carve through endless stretches of arid land, lie the buried secrets of humanity’s earliest chapters. This is the birthplace of Sumer, a civilization that emerged over 7,000 years ago and laid the foundations for much of what we take for granted today. From the invention of the wheel to the first written words scratched into clay tablets, the Sumerians were innovators who transformed a challenging landscape into a thriving hub of culture, law, and technology.

But what sparked this extraordinary leap? For decades, historians and archaeologists puzzled over the rapid rise of Sumerian society, attributing it to everything from trade networks to resourceful pastoralism. Now, a groundbreaking study published in PLOS One in 2025 is flipping the script. Titled “Morphodynamic Foundations of Sumer,” this research by geologist Liviu Giosan of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and archaeologist Reed Goodman of Clemson University reveals that the key wasn’t in the stars or the soil alone—it was in the rhythmic pull of the tides. And in a stunning twist, it confirms that the Sumerian tales of a cataclysmic Great Flood weren’t mere fables but evidence of real environmental upheavals.

This discovery doesn’t just rewrite textbooks; it bridges the gap between myth and science, showing how nature’s forces directly sculpted human destiny.

The Cradle of Civilization | Sumer’s Legacy

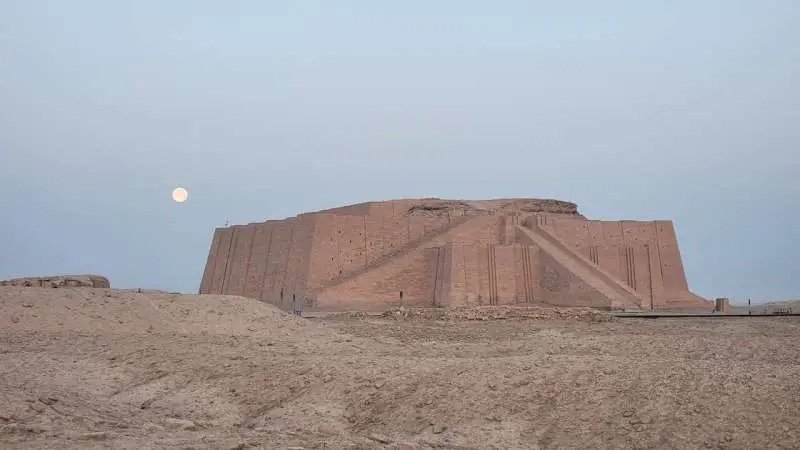

Imagine a world without cities, without written laws, without the concept of minutes ticking by on a clock. That’s the prehistoric void the Sumerians filled, emerging around 4500 BCE in what we now call Mesopotamia, the “land between the rivers.” Cities like Ur, Uruk, and Lagash rose from the marshes, their towering ziggurats piercing the sky as monuments to human ambition.

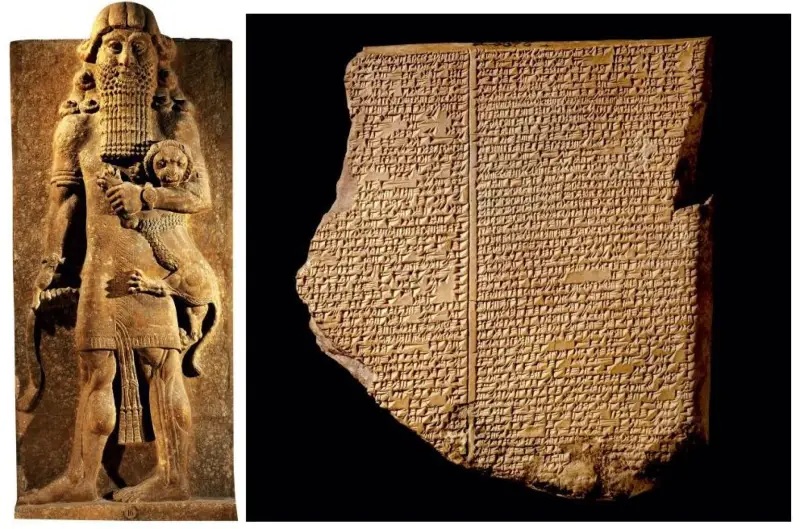

Sumer was a network of city-states, each buzzing with activity. Farmers tended lush fields of barley and dates, artisans crafted intricate jewelry from lapis lazuli imported from distant mountains, and scribes recorded everything from epic poems to mundane grain tallies on cuneiform tablets. This was the dawn of urbanization, where populations swelled into the tens of thousands, demanding organized governance and shared resources.

Inventions that Shaped Humanity

What set the Sumerians apart was their ingenuity. They invented the wheel around 3500 BCE, revolutionizing transportation and pottery-making. Cuneiform writing, starting as simple pictographs for accounting, evolved into a sophisticated script that captured stories, laws, and scientific observations. The Code of Ur-Nammu, predating Hammurabi’s famous laws by centuries, established principles of justice that echo in modern legal systems.

Time itself owes a debt to Sumer. They divided the day into 24 hours and the hour into 60 minutes, based on their sexagesimal (base-60) number system—a legacy still used in our clocks and geometry. Astronomy flourished; they charted the stars, predicting eclipses and seasons. And let’s not forget beer | Sumerians brewed it as a staple, even worshiping a goddess of brewing, Ninkasi.

Yet, beneath these achievements lay a fragile dependence on the environment. The Mesopotamian plain was no Eden—it was hot, dry, and prone to floods. So how did a semi-nomadic people turn this into a powerhouse? The answer, as recent science shows, starts with the sea.

A Revolutionary Discovery | Tides as the Catalyst

Fast-forward to 2025. In a collaboration blending archaeology, geology, and satellite technology, Giosan and Goodman’s study has upended our understanding of Sumer’s origins. Published on August 20 in PLOS One, the paper draws from a new drill core extracted at the ancient site of Lagash (modern Tell al-Hiba), combined with high-resolution satellite imagery and paleoenvironmental data.

The core, a 25-meter-deep snapshot of sediments, revealed layers of marine deposits sandwiched between fluvial ones, painting a picture of a dynamic coastline. Radiocarbon dating and proxies like bromine and sulfur levels confirmed that around 7000 years ago, the Persian Gulf extended far inland, its tides pulsing up the rivers twice daily.

The Study Unveiled

The researchers used Copernicus satellite data to map ancient landforms—fluvial ridges, terraces, and deltaic features—across the Mesopotamian Plain. At Lagash, the drill uncovered evidence of tidal shoals and marine incursions, with dates showing rapid delta advancement between 7000 and 6000 years before present (BP).

Key quote from Giosan | “Our results demonstrate that Sumer was literally and culturally built on the rhythms of water. The cycle of tides, as well as the changes in landscapes over time, were deeply woven into the myths, innovations, and daily lives of the Sumerians.”

This isn’t speculation; it’s backed by microfossils like foraminifera (tiny marine organisms) and ostracods, indicating brackish environments where sea met river. The study proposes that tidal irrigation—where rising tides pushed fresh, silt-laden water upstream—created a natural, low-effort farming system. No massive canals needed at first; short diversions sufficed to flood fields with nutrient-rich water.

As co-author Reed Goodman notes | “The delta in Mesopotamia was restless and changeable. Its land required constant ingenuity and collective effort, leading to the first intensive farming methods and bold social experiments in history.”

Tidal Paradise | The Golden Age of Natural Irrigation

Picture southern Mesopotamia 7000 years ago | not the dusty expanse of today, but a vast, swampy delta where the Persian Gulf intruded deep into the land. The Tigris and Euphrates didn’t just flow to the sea—they danced with it. Tides, amplified by the moon’s gravity, surged inland, carrying fresh water (not salty, thanks to river outflows) up to 200 kilometers from the coast.

This created a “tidal paradise,” as the study describes. Communities like Eridu and Ur thrived in this ecosystem, harvesting unprecedented crops without backbreaking labor. Barley, wheat, dates, and legumes flourished in the fertile silt deposited by each tide.

How Tides Worked Their Magic

The mechanism was elegant | During high tide, water backed up the rivers, flooding low-lying plains. Farmers built simple bunds and canals to channel this into fields, irrigating twice daily. This system was self-sustaining—silt renewed soil fertility, preventing salinization that plagues arid regions.

The result? A demographic boom. Surplus food freed people from subsistence farming. Some became potters, weavers, or traders; others priests or leaders. Specialization sparked innovation, from better tools to early writing for tracking harvests.

Data from the study | The maximum tidal reach (MTR) extended beyond modern Nasiriyah, with the maximum flooding limit (MFL) reaching up to Kut. Figures show the Sumer delta lobe evolving, with tidally influenced zones supporting early Uruk settlements (6000-5200 BP).

This era aligns with the Ubaid to Uruk transition, when villages grew into proto-cities. Tidal abundance explains the “Sumerian takeoff”—prosperity before complex irrigation.

The Turning Tide | Environmental Crisis and Innovation

Nothing lasts forever, especially in a delta. The Tigris and Euphrates carried millions of tons of silt annually, building vast lobes that pushed the coastline seaward. By 6000-5000 BP, the Gulf’s head shallowed, blocking tidal access.

Natural channels silted up; fresh water inflows dwindled. Salinization set in, crops failed, and famine loomed. This wasn’t gradual—it was a crisis forcing adaptation.

Delta Dynamics and the Push for Change

The study maps this shift | Delta progradation (advancement) restricted sea access, turning a tidal regime into a fluvial one reliant on unpredictable river flows. To survive, Sumerians united, constructing massive irrigation networks—canals, dams, reservoirs—spanning hundreds of kilometers.

This required hierarchy | Kings and priests coordinated labor, justifying power through divine mandates. Quote from Holly Pittman, not in the study but referenced in related discussions | “Rapid environmental change has contributed to inequality, political consolidation, and the ideologies of the world’s first urban society.”

By the Early Dynastic period (c. 4900-4350 BP), city-states like Lagash boasted engineered landscapes. The crisis didn’t destroy Sumer; it forged it, turning environmental adversity into societal strength.

Water in the Sumerian Soul | Myths, Gods, and Worldview

Water wasn’t just a resource—it was divine. The study’s morphodynamic lens explains why | Tides shaped daily life, and their loss echoed in lore.

The Epic of Gilgamesh and the Flood

The Great Flood myth, immortalized in the Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2100 BCE), describes gods sending a deluge to wipe out humanity, survived by Utnapishtim (like Noah). The study links this to real events | Storm surges from the Gulf, amplified by tides, caused devastating floods when the sea was closer.

These weren’t metaphors; they were memories of tidal-river interactions gone awry. Biblical Flood tales trace back here, via Babylonian influences.

Enki and the Abzu

Enki, god of water, wisdom, and creation, ruled the Abzu—an underground freshwater ocean mirroring the tidal aquifers. Myths portray him channeling waters for fertility, akin to irrigation mastery.

Water symbolized power; controlling it equated to godhood, bolstering elites. As Giosan states | “The water element was not just a background, but the foundation of their culture.”

Lessons for Other Civilizations

Sumer’s story isn’t unique. The study prompts reevaluation of others | The Indus Valley’s monsoon-dependent deltas, the Maya’s wetland adaptations, Egypt’s Nile floods—all show environment as “director” of history.

In our climate-changing world, it’s a cautionary tale. Rising seas and shifting rivers could reshape societies again. What if modern deltas face similar tidal disruptions?