Beneath the sun-scorched sands of Hawara, in Egypt’s fertile Fayum oasis, lies a mystery that could redefine our understanding of ancient history. For over 17 years, the Egyptian authorities have imposed a strict ban on archaeological excavations at the site of the legendary Egyptian Labyrinth, a colossal underground complex described by ancient historians like Herodotus and Strabo.

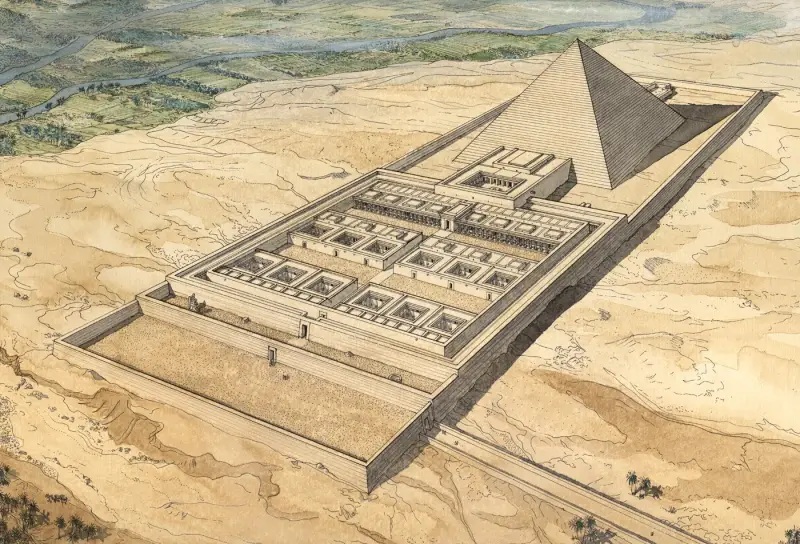

Confirmed by cutting-edge satellite imagery and ground-penetrating radar (GPR), this sprawling structure—covering an estimated 70,000 square meters at depths of 8 to 12 meters—may hold secrets that challenge everything we know about ancient Egyptian civilization. So why is Egypt hiding what could be the greatest wonder of the ancient world?

The Legendary Labyrinth | A Marvel of the Ancient World

Historical Accounts of the Labyrinth

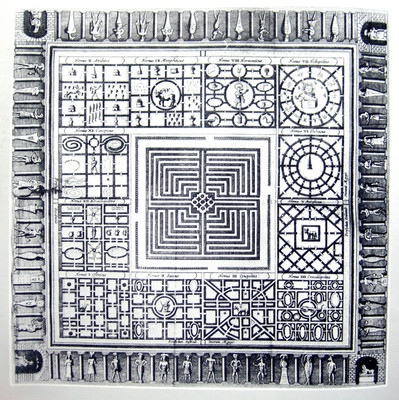

The Egyptian Labyrinth, first documented by the Greek historian Herodotus in the 5th century BCE, was described as a monumental complex surpassing even the pyramids in scale and grandeur. Herodotus, who claimed to have visited the site, wrote of a structure with 3,000 chambers—half above ground, half below—interconnected by intricate passages and adorned with white marble colonnades. He marveled at its twelve covered palaces and the sheer complexity of its design, which he deemed a sacred and perilous space.

Centuries later, the geographer Strabo echoed Herodotus’ awe in his work Geography (Book XVII), noting a memorial plaque at the Labyrinth’s entrance that warned, “Madness or death will find the weak here.” This ominous inscription hinted at the structure’s sacred significance and the dangers lurking within its maze-like corridors. Both historians placed the Labyrinth near the pyramid of Amenemhet III in Hawara, 80 kilometers south of Cairo, in the fertile Fayum oasis—a region historically linked to Egypt’s agricultural prosperity.

Other ancient sources, including Manetho, Diodorus of Sicily, and Pliny the Elder, reinforced these accounts. Manetho, a 3rd-century BCE Egyptian priest, attributed the Labyrinth to Pharaoh Amenemhet III of the 12th Dynasty, calling it his tomb. Diodorus, writing in the 1st century BCE, claimed it remained intact in his time, praising its “cunning and mastery” that made navigation impossible without a guide. Pliny described it as a “most outlandish creation,” with porphyrite columns, monstrous statues, and doors that roared like thunder when opened. These accounts collectively paint a picture of a structure that awed even the most traveled scholars of antiquity.

A Sacred and Forbidden Space

The Labyrinth’s underground chambers were off-limits to visitors, reserved for the tombs of pharaohs and sacred crocodiles, revered as embodiments of the god Sebek. Ancient manuscripts suggest these crocodiles, some reportedly reaching 30 meters in length, roamed the darkened corridors, adding to the site’s mystique. Before major festivals, mystery rituals and sacrifices—including human offerings—were allegedly performed to honor Sebek, reflecting the Labyrinth’s role as a religious epicenter. Its intricate design, plunged into absolute darkness and punctuated by thunderous doors, ensured that only the initiated could navigate its depths, protecting its sacred contents from outsiders.

A Lost Wonder Rediscovered

For centuries, the Labyrinth was dismissed as a myth, a fanciful exaggeration by ancient travelers. However, modern technology has breathed new life into these ancient accounts. In 2008, the Mataha Expedition, led by Belgian researcher Louis de Cordier, used ground-penetrating radar and electrotomography to uncover compelling evidence of a vast underground complex beneath Hawara. Their findings aligned strikingly with Herodotus’ descriptions, revealing a multi-tiered structure with chambers, corridors, and a central atrium connecting multiple levels separated by 20 to 50 meters of rock.

Further confirmation came from Merlin Burrows, a British company specializing in advanced imaging technologies. In 2015, at a closed briefing in Harrogate, their team—led by former Royal Air Force officer Tim Akers—presented satellite and GPR data showing a 70,000-square-meter complex, equivalent to ten football fields. The scans revealed a four-tiered structure, with each level meticulously organized and interconnected. At the heart of this subterranean enigma lies a mysterious 40-meter-tall object dubbed “Dippy,” located in a massive 100×40-meter hall. Its metallic signature, distinct from the surrounding stone and mudbrick, has sparked intense speculation about its purpose and origin.

The Metal Sphinx | The Mystery of “Dippy”

A Puzzling Anomaly

The discovery of “Dippy” is perhaps the most tantalizing aspect of the Labyrinth’s rediscovery. This freestanding object, shaped like the ancient Egyptian shen ring—a symbol of eternity resembling the Greek letter Omega (Ω)—emits a metallic signature that defies conventional archaeological understanding. Surrounded by a moat in the same Omega shape, Dippy’s material composition remains unknown, as Egypt’s ban on excavations prevents closer analysis. Its size and location suggest it could be a monumental artifact, possibly linked to the Labyrinth’s sacred or ceremonial functions.

Connections to Ancient Symbolism

The shen ring, often depicted in ancient Egyptian art as a symbol of divine protection and eternal cycles, raises questions about Dippy’s role in the Labyrinth. Was it a ritual object, a technological relic, or something entirely unknown to modern archaeology? The fact that the surrounding moat mirrors its shape suggests deliberate design, hinting at a deeper symbolic or functional purpose. Some researchers speculate that Dippy could be linked to advanced metallurgical knowledge, challenging the traditional timeline of ancient Egyptian technology.

The Blind Passage and New Discoveries

The Mataha Expedition also revisited findings from the 19th century, when archaeologist Flinders Petrie uncovered a burial chamber beneath Amenemhet III’s pyramid in 1888. Petrie noted a “blind passage” he believed to be a dead end. However, modern scans suggest this passage may lead to a previously undiscovered chamber, potentially flooded by groundwater from the nearby Bahr-Wahbi Canal. This corridor could serve as an entrance to the Labyrinth, offering a pathway to its deepest secrets—if only excavations were permitted.

Why the Ban? Egypt’s Official Stance

Environmental Concerns

The Egyptian authorities cite environmental risks as the primary reason for prohibiting excavations at Hawara. The region’s high groundwater salinity, particularly from the Bahr-Wahbi Canal, poses a threat to artifacts. Exposure to air could trigger rapid corrosion, especially for metallic objects like Dippy. Additionally, the 16-meter layer of sand covering the site acts as a natural preservative, stabilizing the underground structure. Excavating without a comprehensive 3D model—currently unattainable due to research restrictions—could lead to catastrophic collapses, endangering both the site and any artifacts within.

Protecting Historical Narratives

Beyond environmental concerns, some experts believe the ban reflects a desire to control the narrative of ancient Egyptian history. The Labyrinth’s potential to reveal artifacts or technologies that don’t align with established chronologies—such as the mysterious Dippy—could challenge long-held assumptions about the civilization’s capabilities. For a country that relies heavily on its archaeological heritage for tourism and cultural identity, such paradigm-shifting discoveries could be both a blessing and a curse.

The “Closed Zone” Designation

Since 2012, Hawara has been designated a “closed zone” under the pretext of protecting Amenemhet III’s pyramid. This designation has effectively barred foreign researchers and limited local access, stifling further investigation. The Mataha Expedition’s discovery of 3,300 stone fragments, ivory figurines, and inscribed slabs from the era of Amenemhet III only intensified scrutiny, yet the ban remains firmly in place.

Conspiracy Theories | Fact or Fiction?

The Nazi Connection

Among the more speculative theories surrounding the Labyrinth is a rumored Nazi expedition in 1942. According to unverified accounts, German archaeologists searched Hawara for the fabled library of Imhotep, the legendary architect of Pharaoh Djoser’s Step Pyramid. This library, some claim, contained esoteric knowledge linked to the mythical Atlantis. While no concrete evidence supports this story, the idea that Egypt’s authorities are suppressing information to avoid associations with the Third Reich’s occult interests persists in certain circles.

The Missing Siwa Artifact

Another tale involves a French expedition in 1940 that allegedly discovered a metal box—possibly aluminum—in the Siwa oasis, dated to around 2500 BCE. This artifact, said to contain papyri with unusual content, reportedly vanished during transport in 1942. Some speculate that these documents originated from the Labyrinth’s library, adding fuel to theories of a cover-up. While intriguing, these stories lack corroboration and remain firmly in the realm of conjecture.

The Saqqara Discovery

More grounded in reality is a 2020 discovery by Japanese researchers using muon tomography, which revealed a deep labyrinthine network of tunnels and chambers beneath the Pyramid of Djoser in Saqqara, 150 meters underground. The Egyptian authorities classified these findings, further fueling suspicions of a broader effort to conceal underground structures across the country. While not directly linked to Hawara, this discovery underscores the potential for hidden complexes that could reshape our understanding of ancient Egypt.

The Role of Modern Technology in Unlocking the Labyrinth

Satellite and Radar Innovations

The rediscovery of the Labyrinth owes much to advancements in remote sensing. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) satellites, capable of penetrating clouds, sand, and soil, have mapped Hawara’s anomalies without invasive digging. Ground-penetrating radar and electrotomography have provided detailed images of the complex’s multi-tiered structure, confirming its alignment with ancient descriptions. These technologies, originally developed for military applications like submarine tracking and bunker detection, have revolutionized archaeology, offering a non-destructive way to explore forbidden sites.

The Virtual Exploration Project

At University College London (UCL), the A Virtual Exploration of the Lost Labyrinth project aims to reconstruct the Labyrinth using artifacts from the Petrie Museum and existing scan data. However, the project faces significant hurdles due to Egypt’s restrictions on new research. Without access to fresh data, the team relies on incomplete information, limiting the accuracy of their digital model.

The Race Against Time

Merlin Burrows’ scans offer hope that the Labyrinth’s deeper levels, protected by bedrock, remain intact despite flooding in the upper chambers. However, the saline groundwater poses a slow but relentless threat, eroding artifacts over time. The longer excavations are delayed, the greater the risk to the site’s preservation, raising urgent questions about balancing conservation with exploration.

The Labyrinth’s Significance

Ancient Ingenuity

If fully excavated, the Labyrinth could reveal unprecedented insights into ancient Egyptian architecture, engineering, and religious practices. Its scale and complexity suggest a level of sophistication that rivals or surpasses the pyramids, potentially linked to the reign of Amenemhet III, a pharaoh known for his ambitious irrigation projects in the Fayum oasis. The Labyrinth may have served as a ceremonial center, a royal archive, or even a repository for sacred knowledge, as hinted by ancient texts.

Rewriting History

The presence of a metallic object like Dippy raises provocative questions about ancient technology. Could the Egyptians have mastered advanced metallurgy or inherited knowledge from an earlier civilization? Such discoveries could challenge the linear narrative of human progress, prompting a reevaluation of Egypt’s role in the ancient world.

A Global Cultural Treasure

The Labyrinth’s potential as a UNESCO World Heritage Site is undeniable, yet its inaccessibility prevents it from taking its rightful place among the world’s greatest wonders. Its rediscovery could inspire new generations of archaeologists, historians, and tourists, while offering Egypt an opportunity to showcase its unparalleled heritage.