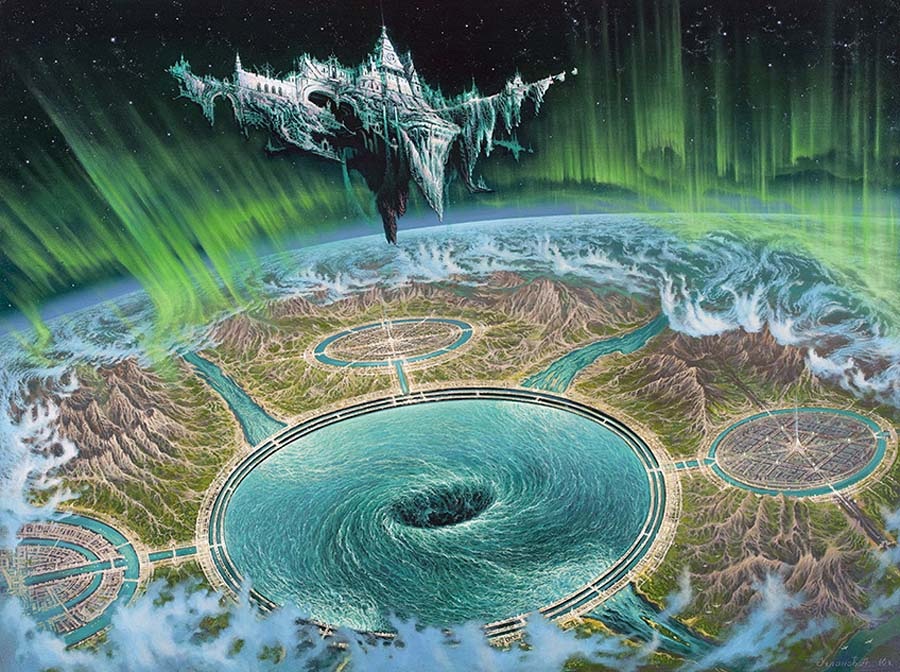

Imagine a vast, thriving continent nestled at the top of the world, where ancient civilizations flourished under the midnight sun. This isn’t just a fairy tale from Greek mythology—it’s Hyperborea, also known as Arctida, a land said to have existed in the Far North, right around the modern North Pole. According to legends, it was a paradise of eternal spring, home to enlightened people who lived in harmony with nature. But then, catastrophe struck: massive cataclysms, floods, and shifting climates sent it plummeting beneath the waves.

Official history tells us this happened tens of thousands of years ago, if it happened at all. Many scholars dismiss it as pure myth, a poetic invention to explain the unknown.

But what if the experts are wrong? What if Hyperborea didn’t vanish in prehistoric times but survived until the Renaissance era, only to disappear in the 16th century? This idea challenges everything we think we know about our planet’s past. Drawing from ancient maps, explorer accounts, and overlooked historical records, a compelling case emerges that Hyperborea was real—and its demise reshaped the world in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Unraveling the Myth of Hyperborea

Hyperborea has captivated imaginations for millennia. The name itself comes from Greek, meaning “beyond the north wind,” a reference to a land far beyond the harsh gales of Boreas. Ancient writers like Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, and Pindar described it as a utopian realm where the sun never set for half the year, and its inhabitants enjoyed long lives free from disease and war. Some even linked it to the gods, suggesting Apollo himself retreated there during winter.

Ancient Legends and Modern Doubts

In classical texts, Hyperborea was placed somewhere north of the known world, perhaps near the Riphean Mountains or the Arctic Circle. Greek myths portrayed it as a bridge between the mortal realm and the divine, with ambassadors from Hyperborea visiting Delphi to offer gifts. But as exploration advanced, these stories were relegated to folklore. Modern historians argue that Hyperborea was likely inspired by vague reports of northern tribes or exaggerated tales from traders.

Yet, skeptics of this dismissal point to geological evidence. The concept of Arctida, a hypothetical ancient continent in the Arctic, has been proposed by some scientists based on seabed mapping and plate tectonics. Could this be the scientific echo of the Hyperborean legend? Theories suggest that rising sea levels or tectonic shifts could have submerged such a landmass, but the timeline is hotly debated. While mainstream views peg any such event to the end of the last Ice Age around 12,000 years ago, alternative researchers claim it happened much more recently—perhaps as late as the 1500s.

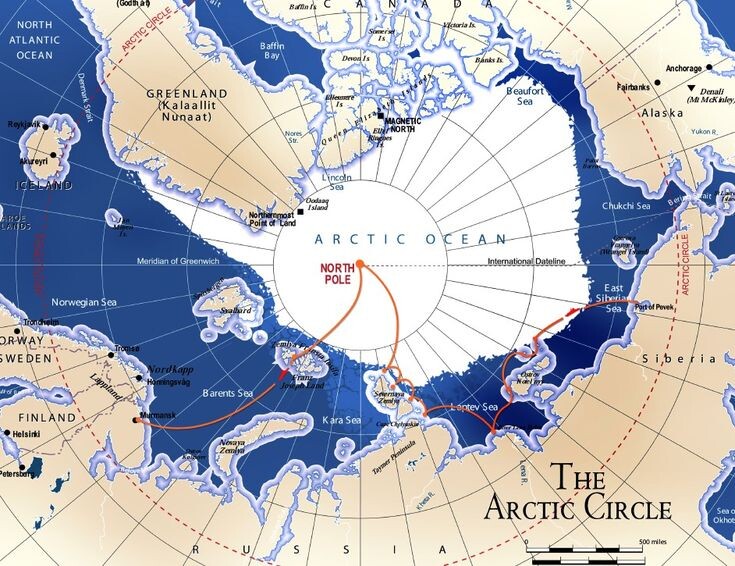

This brings us to a crucial question: If Hyperborea sank so long ago, why do 16th-century maps show land at the North Pole in stunning detail? These aren’t crude sketches; they’re the work of renowned cartographers who relied on eyewitness accounts from sailors, merchants, and diplomats. Let’s examine these maps and what they reveal.

The Cartographic Clues: Maps That Defy Official History

The 16th century was a golden age of mapmaking, fueled by the Age of Discovery. Explorers like Columbus and Magellan expanded Europe’s horizons, but the Far North remained shrouded in mystery. Still, several maps from this era depict a continent-like landmass at the North Pole, complete with rivers, mountains, and coastlines. These aren’t isolated anomalies—they appear consistently across works by European and even Arab geographers.

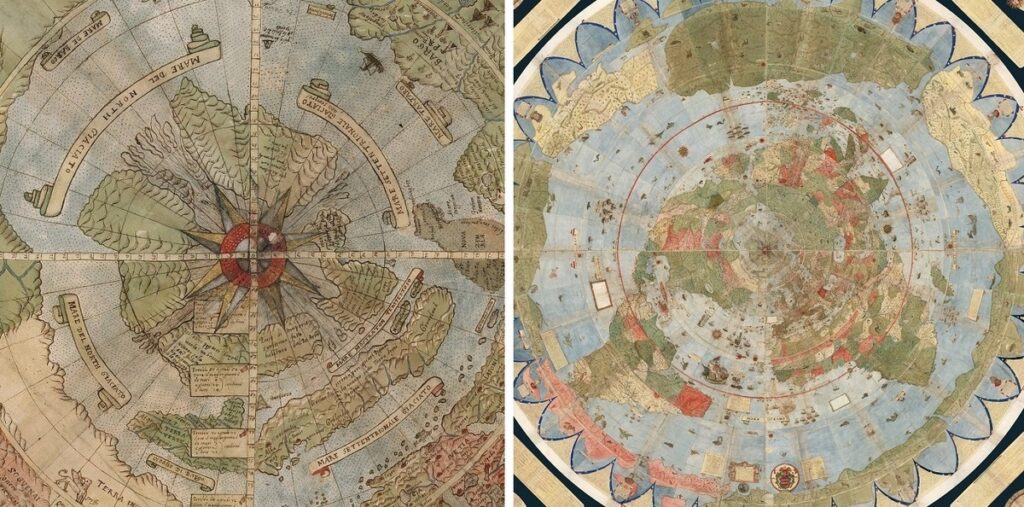

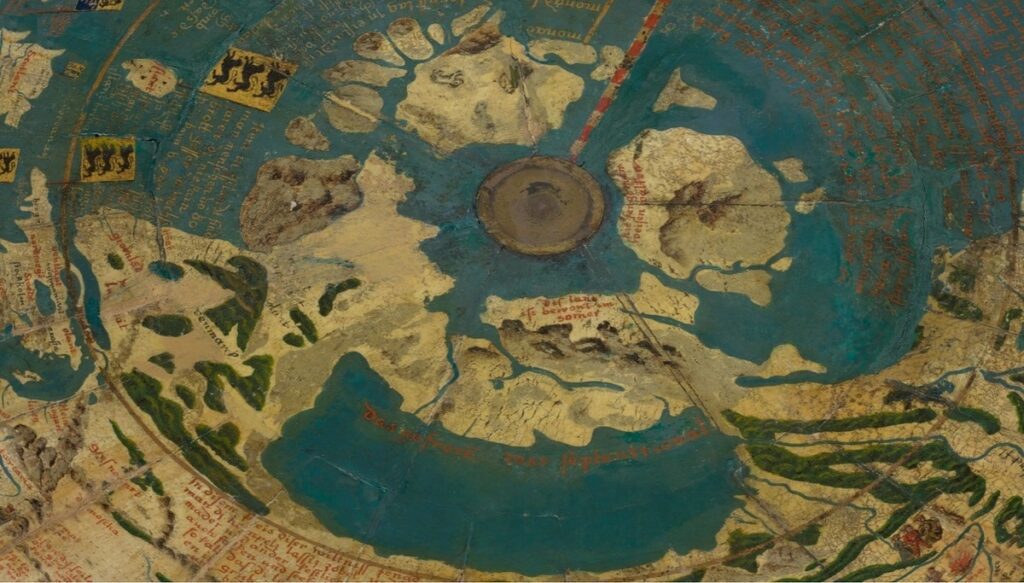

Gerard Mercator’s 1569 Masterpiece

Gerard Mercator, the Flemish cartographer whose projection is still used today, created one of the most influential world maps in 1569. In the northern hemisphere, he illustrates a large landmass surrounding the North Pole, divided into four islands by inward-flowing seas. At the center sits a massive magnetic rock, the Rupes Nigra, believed to draw compass needles northward. This depiction wasn’t Mercator’s invention; he drew from reports by travelers and earlier sources, including the lost Inventio Fortunata, a 14th-century book describing Arctic voyages.

Mercator’s map shows the Arctic coast of Russia in remarkable detail, including the future Bering Strait (called the Strait of Anian). Greenland appears with mountain ranges unknown until the 20th century and numerous settlements. Critics might call this fantasy, but Mercator was no fabulist. As the era’s most respected mapmaker, he cross-verified data from captains, merchants, and diplomats. His accuracy in other regions—like Europe and Africa—lends credibility to his Arctic portrayal.

Johannes Ruysch’s 1507 Vision of the North

Even earlier, in 1507, German cartographer Johannes Ruysch published a world map showing four islands encircling the North Pole. These lands feature mountains, green shores, and rivers, suggesting a habitable environment. Ruysch, who may have sailed with John Cabot, incorporated reports of polar islands and strong currents flowing toward the Pole. His map influenced later works, including Mercator’s, and challenges the idea of an eternally frozen Arctic.

Ruysch’s depiction aligns with legends of Hyperborea as a fertile land. One island north of Greenland is labeled “Insula,” hinting at unknown territories. If this was mere speculation, why did Ruysch include such specifics? Perhaps he had access to now-lost accounts from Viking or earlier explorers.

Oronteus Finaeus and the Ice-Free Poles (1531)

French mathematician Oronce Fine (Latinized as Oronteus Finaeus) produced a 1531 world map that not only shows Arctida in the north but also an ice-free Antarctica in the south. The southern continent appears with rivers and mountains, as if mapped during a warmer epoch. This has fueled theories of ancient advanced civilizations or lost knowledge from pre-flood times.

Finaeus’s northern landmass is detailed, with coastlines that mirror modern Arctic bathymetry if sea levels were lower. Antarctica wasn’t officially discovered until 1820, yet here it is, sans ice sheet. Some researchers suggest Finaeus drew from ancient sources, possibly Egyptian or Phoenician maps preserved in libraries.

Haji Ahmed’s Arab Perspective (1559)

Not limited to Europe, the 1559 cordiform (heart-shaped) map by Tunisian cartographer Haji Ahmed also depicts Arctida. Created in Venice but attributed to an Ottoman scholar, it shows detailed northern lands, echoing Mercator and Finaeus. Ahmed’s work blends Islamic geography with European discoveries, suggesting widespread knowledge of a polar continent.

This cross-cultural consistency is striking. Why would an Arab geographer invent the same “mythical” land as his European counterparts? It points to shared sources, perhaps from medieval travelers or ancient manuscripts.

Urbano Monte’s Detailed 1587 Planisphere

Italian cartographer Urbano Monte’s massive 1587 manuscript map, assembled from 60 sheets, offers one of the most intricate views of Arctida. Spanning over nine feet, it depicts the North Pole with rivers, mountains, and even mythical creatures, alongside a detailed Antarctica predating its discovery by centuries. Monte claimed his map was meant to be viewed from above the North Pole, a novel perspective.

Recent digital assembly of Monte’s sheets reveals astonishing accuracy in some areas, fueling speculation about lost technologies or surveys. If Hyperborea was sinking gradually, Monte’s map might capture it in its final stages.

These maps collectively paint a picture of a real Arctida, not a figment of imagination. By the early 17th century, however, such lands vanish from cartography, replaced by “Terra Incognita” and ice.

Greenland: From Blooming Paradise to Frozen Wasteland

Greenland’s name isn’t ironic—historical evidence suggests it was once far greener. Viking settlements thrived there from the 10th to 15th centuries, with farms and churches. But what if this verdant phase extended into the 16th century?

The Zeno Brothers’ Map of 1558

Published in 1558 by Nicolò Zeno, this map claims to document 14th-century voyages by his ancestors. It shows Greenland with dozens of settlements, including cities along its coasts. The map also features phantom islands like Frisland, but its Greenland details align with Norse sagas of a habitable land.

Zeno’s accounts describe sailing freely to Greenland’s shores, where thriving communities existed. By the late 1500s, however, a Little Ice Age had set in, covering the island in glaciers. This shift coincides with Hyperborea’s alleged disappearance.

The Barents Expedition: A Clash of Maps and Reality

In 1596, Dutch navigator Willem Barents set out to find a northern route to China, armed with old maps showing ice-free Arctic waters. Confident from these charts, he expected smooth sailing. Instead, his ship became trapped in ice near Novaya Zemlya, forcing the crew to winter in harsh conditions.

Barents couldn’t reconcile his maps with the frozen reality. Where did his information come from? Likely from earlier 16th-century sources depicting an open Arctic. This suggests a rapid climatic change, perhaps triggered by Hyperborea’s sinking and resulting floods.

Pioneers of the North: Dezhnev and the Bering Strait

Russian Cossack Semyon Dezhnev is credited with discovering the Bering Strait in 1648, sailing from the Arctic to the Pacific. But maps like Mercator’s showed the strait (as Anian) a century earlier. Dezhnev’s voyage, 80 years before Vitus Bering, confirms navigable northern routes in the recent past.

The Controversial Maldonado Manuscript

A 16th-century manuscript attributed to Spanish navigator Alonso del Castillo Maldonado describes sailing the northern route around North America, encountering Russian ships in the Strait of Anian. (Note: Historical records link Maldonado to southern expeditions with Cabeza de Vaca, but fringe theories suggest a northern voyage.) It claims a spacious harbor where 500 ships could anchor, and meetings with merchants en route to Arkhangelsk. Dismissed as a forgery by many, it nonetheless echoes accounts of bustling Arctic trade before the ice took hold.

If true, it implies the northern passage was routine in the 1500s, only becoming impassable after cataclysms.

The Great Floods and Gradual Sinking

Evidence points to Hyperborea’s demise as gradual, spanning decades in the 16th century. Maps evolve from full depictions early on to partial ones later, vanishing entirely by 1600. Europe suffered massive floods around this time, with waves from the north devastating coasts for nearly a decade.

Theories link this to polar shifts or melting ice from a warmer Arctic, flooding lowlands and altering ocean currents. Black Sea deluge hypotheses suggest similar events elsewhere, perhaps echoing a global catastrophe.

Rewriting History: The Role of Scaliger and the Vatican

Why isn’t this in textbooks? Some argue it ties to a deliberate historical revision. In the late 16th century, Joseph Justus Scaliger, under Vatican influence, developed a new chronology of world history. His work standardized dates, but critics claim it compressed timelines to fit religious narratives, erasing inconvenient events like recent polar lands.

Post-catastrophe, the Vatican and emerging powers allegedly rewrote chronicles to consolidate control, burying evidence of Hyperborea. This “new reality” persists, but old maps and accounts whisper the truth.

Choosing Between Maps and Myths

The evidence—from Mercator to Monte, Barents to Dezhnev—suggests Hyperborea existed until the 16th century, its loss ushering in the Little Ice Age and reshaping global navigation. Official history calls it myth, but the maps don’t lie. Perhaps it’s time to revisit the North Pole’s secrets. What do you think—ancient legend or hidden truth?