In the heart of Ecuador’s untamed wilderness, a remarkable discovery in 1984 shook the foundations of archaeology and ignited debates that continue to echo today. During one of his forty expeditions across South America, intrepid archaeologist Elias Sotomayor stumbled upon a hidden cave harboring an extraordinary cache of ancient artifacts.

Known as the Elias Sotomayor Collection, this trove of approximately 180 objects offers a tantalizing glimpse into a forgotten era, challenging everything we thought we knew about human history. From glowing pyramids to ancient maps depicting lost continents, the collection is a labyrinth of enigmas, each artifact whispering secrets of a civilization—or civilizations—lost to time.

The Discovery | A Cave of Wonders

Elias Sotomayor was no stranger to the rugged terrains of South America. His decades of exploration had honed his instincts for uncovering the past’s hidden treasures. In 1984, guided by whispers of local lore and his unrelenting curiosity, he ventured into a remote cave in Ecuador’s dense jungle. What he found inside was beyond imagination | a meticulously arranged collection of artifacts, concealed by an unknown hand in the distant past. Local residents had occasionally unearthed stray objects in the same cave, but none had grasped the magnitude of what lay hidden. Sotomayor’s discovery was a game-changer, a portal to a world that predates recorded history.

The cache comprised around 180 items, each a masterpiece of ancient craftsmanship. There were intricately carved figurines, stone amulets etched with cryptic symbols, and ceremonial objects that defied easy interpretation. Among them stood a large stone slab, its surface covered in enigmatic lines. At first glance, the markings seemed abstract, perhaps decorative. But as Sotomayor and his team studied it, a revelation emerged | this was no ordinary stone—it was potentially the oldest map of the world ever discovered.

The Ancient Map | A Glimpse of a Lost Earth

The stone slab, now a centerpiece of the Sotomayor Collection, is a cartographic marvel. Its surface traces the outlines of continents and major islands familiar to modern eyes—Africa, Australia, the Americas. Yet, it includes two anomalies that set it apart | two additional landmasses, one in the Pacific Ocean and another in the Indian Ocean. These mysterious continents, absent from today’s geography, sparked intense speculation. Were they errors? Artistic flourishes? Or did they depict a world tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of years ago, when Earth’s surface looked radically different?

Sotomayor hypothesized that the map was not a mistake but a snapshot of a prehistoric Earth, possibly from an era when now-submerged landmasses were above water. Some researchers have linked these depictions to theories of lost continents like Lemuria or Mu, fabled lands swallowed by the oceans in ancient cataclysms. While such ideas remain speculative, the map’s precision and age suggest it was created by a culture with advanced knowledge of geography—knowledge that challenges the timelines of mainstream archaeology.

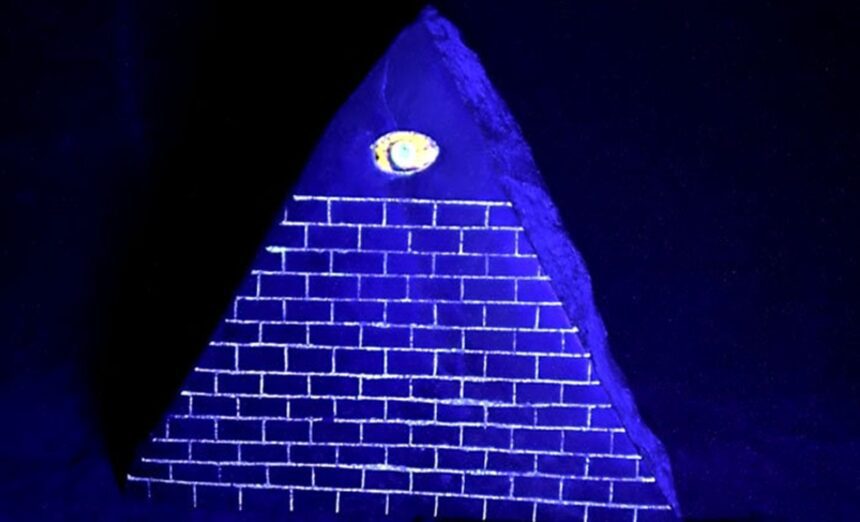

The Glowing Pyramid | A Prophetic Artifact

While the map captured imaginations, another artifact stole the spotlight | a thirteen-tiered pyramid, roughly the size of a small sculpture, adorned with an eye-like inlay near its upper third. This pyramid, crafted with uncanny precision, was no ordinary relic. When exposed to ultraviolet light, the inlay emitted a haunting glow, a phenomenon that baffled scientists. Traces of luminescence were also detected at the joints of the pyramid’s blocks, hinting at the use of an unknown material or technology to bind them. The artifact’s eerie radiance seemed to pulse with purpose, as if it were more than a mere object—it felt alive with meaning.

At the pyramid’s base, an inscription and an image were etched in what appeared to be pure gold. The image meticulously replicated the constellation Orion, its stars aligned with startling accuracy. The inscription, when translated, delivered a chilling prophecy | “The Son of the Creator is coming.” These words, paired with the celestial imagery, suggested a message of cosmic significance, perhaps tied to a messianic figure or an event foretold by its makers. The pyramid’s craftsmanship and materials pointed to a culture of extraordinary sophistication, one capable of blending art, science, and spirituality in ways modern minds struggle to comprehend.

The Laboratory Shock | An Unthinkable Age

Eager to unravel the pyramid’s secrets, Sotomayor sent the artifact—and others from the collection—to laboratories in London, New York, Budapest, and Quito for rigorous analysis. The results were staggering | the artifacts were dated to between 16,000 and 18,000 years old, with the glowing pyramid clocking in at approximately 17,800 years. This placed them in the Upper Paleolithic period, a time when humans were supposedly limited to rudimentary tools and nomadic lifestyles. The notion that a culture could produce such sophisticated objects—complete with glowing materials, precise astronomy, and a written language—defied everything archaeology had established.

The inscription’s language added another layer of mystery. The symbols, though unfamiliar, were not unique to Ecuador. Similar scripts had been documented on artifacts across the globe | in Malta’s megalithic temples, Colombia’s ancient ruins, Turkey’s Göbekli Tepe, Australia’s rock art, and sites in the Mediterranean, France, and Calabria. These parallels suggested a shared cultural or linguistic tradition that spanned continents thousands of years before the rise of modern civilizations. Linguist Kurt Schildmann, a leading authority on such scripts, had deciphered over 300 inscriptions worldwide, linking them to a proto-language that predated known writing systems. His work implied that a global network of advanced societies existed in deep antiquity, a concept that turned history on its head.

The Backlash | A Researcher Shunned

Initially, the archaeological community greeted Sotomayor’s find with excitement. Proposals poured in to exhibit the collection in prestigious museums across Europe, North America, and South America. Historians marveled at the artifacts’ craftsmanship, and plans were made to showcase them as relics of pre-Columbian cultures, perhaps 2,000 to 3,000 years old. Such an age would have fit neatly into accepted historical frameworks, posing no threat to established narratives.

But the laboratory results changed everything. An age of 16,000 to 18,000 years was unthinkable—it suggested a level of cultural and technological advancement that contradicted the gradualist model of human development. Museums began to retract their offers, wary of endorsing finds that could upend their credibility. Even Sotomayor’s colleagues, once supportive, distanced themselves, unwilling to stake their reputations on such controversial claims. The glowing pyramid, with its prophetic inscription and celestial imagery, became a lightning rod for skepticism, dismissed by some as too fantastical to be true.

Sotomayor, however, was undeterred. A principled researcher, he believed the public deserved to know the truth, no matter how inconvenient. When major institutions closed their doors, he turned to commercial museums, some of which agreed to host exhibitions. Yet, these displays drew meager crowds—sometimes as few as 100 visitors per day—far from the global recognition he sought. The artifacts, despite their profound implications, remained on the fringes of mainstream awareness.

A New Custodian | The Legacy Continues

Frustrated but resolute, Sotomayor eventually entrusted his collection to Klaus Dona, a specialist in ancient artifacts with a passion for unconventional archaeology. Dona saw the collection’s potential to rewrite history and subjected it to further analysis, leveraging advances in laboratory technology. His findings corroborated Sotomayor’s earlier results and revealed additional nuances. The artifacts spanned multiple eras, though they shared a consistent craftsmanship. The youngest item, a disk inscribed with celestial patterns, was dated to around 12,000 years old. The glowing pyramid remained the eldest at 17,800 years, its authenticity beyond question.

Dona’s efforts to bring the collection to a wider audience met with similar obstacles. The artifacts’ age and implications made them a hard sell for mainstream institutions, which preferred safer, less disruptive narratives. Yet, the collection found a niche among alternative researchers, ancient astronaut theorists, and curious minds eager to explore the boundaries of human history. Online forums, documentaries, and blogs began to buzz with speculation about the glowing pyramid, the ancient map, and the prophecy of “The Son of the Creator.”

The Artifacts’ Enduring Mysteries

The Elias Sotomayor Collection is a treasure trove of unanswered questions. Who created these objects, and why were they hidden in an Ecuadorian cave? What culture, or network of cultures, spanned the globe 18,000 years ago, leaving traces from Australia to the Mediterranean? How did they achieve such feats—glowing materials, precise astronomy, a written language—at a time when humanity was supposedly primitive? And what did they mean by “The Son of the Creator is coming”? Was it a prophecy of a divine figure, an extraterrestrial visitor, or a metaphor for a transformative event?

The glowing pyramid, with its Orion imagery, invites comparisons to other ancient sites, like Egypt’s pyramids, which also align with the constellation. The map’s depiction of lost continents echoes myths of Atlantis, Lemuria, and other sunken lands, fueling speculation about cataclysms that reshaped Earth’s surface. The shared script across continents suggests a level of global connectivity that defies conventional timelines, hinting at a lost golden age of human civilization.

Why It Matters Today

In 2025, the Elias Sotomayor Collection remains a touchstone for those questioning the official story of human history. It challenges us to reconsider our origins, to imagine a past far richer and more complex than textbooks suggest. While mainstream archaeology dismisses the artifacts as anomalies—or worse, fabrications—their age, craftsmanship, and global parallels demand serious inquiry. Advances in technology, from AI-driven linguistic analysis to high-resolution material testing, could unlock new insights, potentially vindicating Sotomayor’s vision.

For now, the collection endures as a beacon of possibility, inviting adventurers, scholars, and dreamers to explore its mysteries. The glowing pyramid, the ancient map, and the prophecy of “The Son of the Creator is coming” are more than relics—they are keys to a past we’ve only begun to understand. As we stand on the cusp of new discoveries, the Elias Sotomayor Collection reminds us that history is not a closed book but a story still being written.